During excavations in October 2006, a crane operator discovered a fossil tusk in a sandpit in Milia. He contacted Professor Evangelia Tsoukala of Aristotle University. She is a paleontologist, specializing in mammals, and had already completed four Pliocene mammal excavation projects in the Milia region, all of which were quite amazing. One of them had resulted in the discovery of the longest pair of tusks in the world.

These belonged to a mastodon, with the scientific name Mammut borsoni, and measured 4.39 m each.

The tusks are almost straight, slightly curved, and, in a living mastodon, would protrude horizontally just in front. This proboscis differed from other species, such as modern elephants, by having a different body shape. It was much more elongated, while its teeth and metabolism were optimized for browsing twigs and leaves.

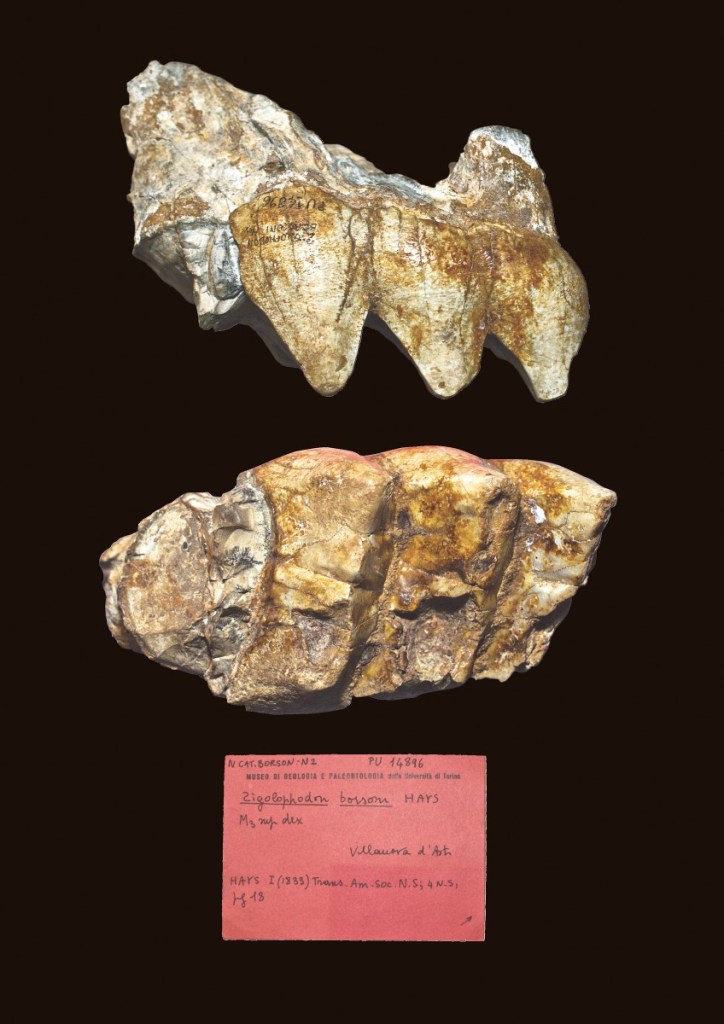

borson mastodon

In honor of Mr. Borson, he named this species Mastodon borsoni. Today this species is included in the genus Mammut and therefore the current correct name is Mammut borsoni. Both Mammut borsoni and Mammut americanum belong to the family Mammutidae, subfamily Mammutinae, being zygodontic mastodons, with molars showing typical comb-shaped ridges. M. borsoni was a huge, robust pachyderm, with male bulls reaching a shoulder height of almost 4 m and some developing giant tusks. It is also the largest known mastodon. Borson’s mastodon, found in both Europe and Asia, became extinct towards the end of the Pliocene between 2.5 and 3 million years ago, while the American mastodon survived, at least until the beginning of the Holocene, about 10,000 years ago. .

We were very lucky to be in Greece participating in the 12th International Cave Bear Symposium and studying Evangelia Tsoukala’s collections when this new discovery was made. This opportunity fell directly into our hands. Both tusks, still in situ, were still being excavated and a tape measure revealed that one was at least 5m in length. That certainly required more research. Evangelia Tsoukala included us in an excavation plan that would take place in July 2007, as there could be much more to discover. The contractor agreed, although reluctantly, to postpone excavation activities in that part of the sandpit.

We were invited to participate in the excavation which began on July 17, 2007. There was intense debate about which part should be discovered first and how to proceed in general. The highly motivated excavation team, consisting of about 12 students, was led by the principal investigator, obviously Professor Evangelia Tsoukala, in close coordination with the co-principal investigator, Dick Mol.

To quickly reach the layers where the fossil remains were embedded about 2.5 million years ago, we used a large excavator to remove the layer of sand. The next day, the first tusk was completely exposed and the second was located and found to be slightly shorter. Unfortunately, the state of conservation was not very good and, therefore, recovery would be very delicate. Meanwhile, it turned out that the 8 x 4 m excavation area, nicely marked with red and white marker tape, contained many more remains of the original owner of these giant tusks. And a part of the skeleton was recovered in the following days under a scorching sun, with temperatures of up to 45°C.

In addition to the giant tusks, parts of the upper jaw (with a splendid molar) and, somewhat later, the lower jaw with molars were discovered. Although broken, it was in excellent condition. This jaw had lost the lower fangs, but the tusk sockets were well preserved. Mammut borsoni had rather large lower tusks with a diameter of 6 to 8 cm at the symphysis of the jaw. The last and penultimate molars are present, revealing not only that this mastodon must have been an explorer, but also something about its age when it died. From these particular fossil remains, we conclude that his age must have been between 25 and 30 years at the time of his death. The enormous limbs reveal the enormous dimensions of this bull in its prime. These discoveries are unique and very spectacular.

That day, some digital photographs were sent to the BBC and, an hour later, appeared on the BBC news website. The Milia-5 mastodon was now world news. More requests for more photographs and information from around the world followed, which kept the team busy. However, there was no time to deviate too much, as there was a deadline to meet: Evangelia Tsoukala had an appointment with the local authorities of the Grevena prefecture on Saturday, July 28. They were going to examine the results of the excavation team and the tusks were to be properly preserved and displayed by then in the small paleontological exhibition center in Milia.

All unearthed remains had to be measured and drawn, which is meticulous work. No data should be lost. All parts of the skeleton (about 30 in total) then had to be plastered to protect them and prevent further damage during transport to the museum. These fossils had been subjected to high pressure due to the weight of the almost 20 m of sand layers that covered them, which in many cases caused deformations.

Consequently, the tusks broke into several pieces and their enormous length prevented the crew from collecting and transporting them all in one piece. These activities also had to be carried out in scorching heat and the work lasted until 10:30 p.m. Only drinking many liters of cold water kept the crew going.

But a deal is a deal, and on Saturday afternoon, at 17:00 sharp, both tusks (a matching right and left pair) were moved into position in Milia’s magnificent little museum. Their sizes, measured along the outside of the curvature (i.e. the bottom surface) are 4.58 m and 5.02 m respectively. Therefore, these are the longest tusks in the world – another new world record.

One wonders how an animal could live with those fangs. How could they have maneuvered them? The sheer inertia of its mass would cause significant complications when turning, not to mention avoiding obstacles, such as rocks and trees. However, unlike elephants, the tusks do not point downward but rather forward and a third of the tusk is also embedded in the dental cavity. Furthermore, the animal was a large bull in its prime, with an estimated shoulder height of 3.30 to 3.50 m.

Thus, the Milia paleontological exhibition center acquired a unique specimen that attracts visitors from afar. However, they do not come only to see Borson’s mastodon, but also the remains of other fossil mammals, collected in recent years and exhibited in the museum. Some are contemporaries of the mastodon: antelopes, rhinos and a saber-toothed cat, also excavated by Professor Tsoukala’s team. Also found are remains of a second species of mastodon, Anancus arvernensis, the Auvergne mastodon (see box).

The Auvergne mastodon – Anancus arvernensis

The Auvergne mastodon – Anancus arvernensis (Croizet & Jobert, 1828) – is a bunodont mastodon, which has molars with blunt dental protuberances that are paired, aligned side by side, forming transverse ridges. These molars suggest that the mastodon had a diet of softer foods, such as leaves, fruits and small twigs.

The worn nubs of the upper jaw molars form a cloverleaf pattern in profile, making them easy to distinguish from the lower molars. Also characteristic of this species are the relatively small and barely bent fangs (Anancus = without curvature). Furthermore, the fangs of the lower jaw are not present in many specimens, while the fangs of the upper jaw are covered by a thin layer of enamel. As stated, they are almost straight and slightly bent outwards.

The discovery of the world’s longest tusks has had a significant impact on the Milia paleontological center. This has resulted not only in more visitors, but also in a greater supply of fossil remains, from a source that readers may not have expected: local shepherds. They are the best eyes and ears of the paleontologists around the town.

As the sheep wander the hills, they trample the ground with their thin feet, sometimes uncovering fossil remains. And several local shepherds have found some very interesting fossils. They are now asked to bring them to the museum, along with information about the location and conditions in which they were found. Every time Professor Tsoukala is in Milia, she explores the area, such as during the summer of 2008. A shepherd reported finding bones on a certain slope. Closer investigation revealed that it was the skull of an extinct species of rhinoceros, discovered by trampling sheep, and a small team of students and experts headed to the area. Hurry was necessary as sheep tend to travel the same paths over and over and could have damaged or even shattered the skull.

The expedition returned in the afternoon and in the back of the car was a delicate, almost complete skull of a Pliocene rhinoceros. The location of the discovery was documented with GPS for its relocation for subsequent exploration. After all, it could be that a complete rhino skeleton was hidden in the ground there. Time will tell.