One of the more interesting mysteries about the Giza pyramids, the most famous and visited relics from ancient Egypt, is their location. They were not constructed near a fertile oasis or on some other piece of attractive land, as would have been expected given their obvious importance as monuments. Instead, they were built along a narrow strip of harsh desert land that was also chosen as the building site for more than two dozen other Egyptian pyramids.

This curious fact has long puzzled archaeologists and Egyptologists. But a new study just published in the journal Communications Earth & Environment offers a perfectly logical explanation for this apparent anomaly.

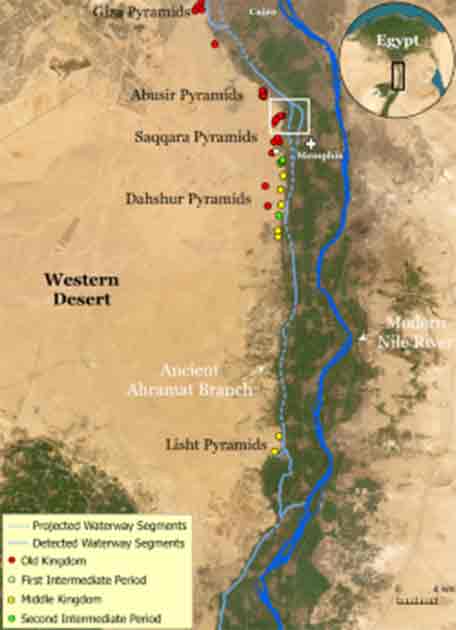

In their enlightening paper, a multidisciplinary team of researchers from Egypt, the United States and Australia present evidence that the Giza pyramids and 28 other such structures were originally built beside a 40-mile (64-kilometer) stretch of a branch of the Nile River that has been buried beneath farmland and desert for more than two millennia. The researchers have named this extinct Nile tributary the Ahramat Branch, with Ahramat meaning ‘pyramids’ in Arabic.

The banks of this long-lost waterway once flowed through the foothills of the Western Desert Plateau on the eastern edge of the Sahara Desert, giving the ancients access to land that was judged a perfect location for pyramid construction.

The water course of the ancient Ahramat Branch borders a large number of pyramids dating from the Old Kingdom to the Second Intermediate Period, spanning between the Third Dynasty and the Thirteenth Dynasty. (Eman Ghoneim et al./Nature)

A Hidden River Found Deep in the Egyptian Desert

From approximately 2,700 BC to 1,700 BC, ancient Egyptian cultures constructed 31 pyramids over between Giza and the village of Lisht to its south. While the land around the pyramids has long been dry, having been completely swallowed up by Egypt’s Western Desert, sedimentary evidence has suggested that when the Nile was fuller it may have split into several different branches, one of which may have flown near the pyramid fields. However, the sedimentary evidence has not been considered conclusive, and there were no other geological signs detected that showed a river had once run close to the pyramids.

Eman Ghoneim studies the surface topography of the section of the ancient Ahramat Branch located in front of the Pyramids of Giza and the Great Sphinx. (Eman Ghoneim/Nature)

Determined to examine the question of ancient Nile pathways more in-depth, the team of researchers involved in the new study, led by geologist Eman Ghoheim from the University of North Carolina-Wilmington, studied satellite imagery, geophysical data and the results of deep sample coring to search for river channels near the pyramids. This combination of technologies produced excellent results, and the researchers were able to identify the remnants of the Ahramat Branch riverbed buried deep beneath Egypt’s desert landscape.

Looking back into the geological record, the researchers were able to link the silting in and disappearance of this branch of the Nile with an increase in windblown sand caused by a long-term drought that began about 4,200 years ago. It would have taken a few centuries before the Ahramat would have been filled in completely, making it no longer navigable.

There are indications that tectonic activity in the region actually caused the riverbed of the branch to gradually shift eastward over time, which likely accelerated the silting process. But while it the Ahramat was flowing, it would have run very close to the sites where the pyramids of Egypt were built, in and around the ancient Egyptian capital city of Memphis.

The Step Pyramid of Djoser, constructed during the Third Dynasty. (Eman Ghoneim/Nature)

Intriguingly, the researchers uncovered clear evidence linking the Ahramat Branch with the construction of this astonishing ancient monuments, in the form of highly suggestive landscape modifications.

“Many of the pyramids, dating to the Old [2,700—2,200 BC] and Middle Kingdoms [2,040—1,782 BC], have causeways that lead to the branch and terminate with Valley Temples which may have acted as river harbors along it in the past,” the researchers wrote in their Communications Earth & Environment article. “We suggest that the Ahramat Branch played a role in the monuments’ construction and that it was simultaneously active and used as a transportation waterway for workmen and building materials to the pyramids’ sites.”

Given the physical challenges and astonishing logistical complexity of pyramid construction, it might be expected they would be erected near Nile-connected waterways, where materials could be moved more rapidly and efficiently than on land, and possibly across long distances.

In Ancient Egypt, the Nile was the True King

Ultimately, the researchers point out, their findings offer definitive proof of just how crucial the Nile River was to the development of ancient Egypt. When its flow rate and volume were at their highest, ancient Egypt reached the pinnacle of its cultural and economic prosperity. It would be expected that the building of the pyramids would be connected to the Nile in some way, and this new study shows that to have been the case.

“Our finding has filled a much-needed knowledge gap related to the dominant waterscape in ancient Egypt,” the researchers explained, “which could help inform and educate a wide array of global audiences about how earlier inhabitants were living and in what ways shifts in their landscape drove human activity in such an iconic region.”