Speculation that aliens might exist dates back to philosophers in ancient Greece, but it was the middle of the 20th century when people’s imaginations really began to run riot — suddenly ‘little green men’ were everywhere in popular culture.

Although the use of the phrase is believed to have originated in 1908, it was between the 1920s and 50s that green Martian characters were plastered all over the covers of science fiction magazines and later people’s TVs.

The reality is that if extraterrestrial life does exist in our solar system it will be of a more simpler variety, perhaps hidden in Venus’ clouds, beneath Mars’ surface or in the vast underground oceans of one of Saturn’s icy moons.

But where else is the best bet of finding it? MailOnline speaks to a number of experts to find out.

Mars

The most obvious candidate for extra-terrestrial life either past or present.

Scientists know the Red Planet was once habitable because billions of years ago it had lakes and rivers of liquid water on its surface, as well as a much thicker atmosphere than the thin one it has now.

But although the conditions were right for life to emerge, is that actually what happened?

Scientists have been trying to find out since the 19th century, although the answer has so far eluded them. Telescopes and probes have offered clues, while NASA has also deployed rovers to hunt for evidence over the past two decades.

Opportunity and Curiosity began the work, but today that baton has very much been handed over to Perseverance and its accompanying Ingenuity helicopter, which touched down on the Red Planet in February 2021.

Car-size robot Perseverance, nicknamed Percy, has so far collected 18 samples of rock and regolith (broken rock and soil) from the Jezero Crater where a river flowed billions of years ago.

When these sample tubes are eventually collected and returned to Earth by a European spacecraft some time in the 2030s, it could help scientists determine whether microbial left ever existed in the region.

If there are signs of ancient life, it is also possible that there are still alien microbes on Mars today, although these would more likely be underground rather than on the surface.

Several studies have previously used radar observations to show that reservoirs of liquid water probably exist just over a mile below the surface, but it would take future exploration – and likely a tricky mission – to try and establish once and for all if life exists there.

Professor Andrew Coates, from the Department of Space & Climate Physics at University College, said the UK-built Rosalind Franklin rover could help with this.

‘We’re searching for evidence of biomarkers with the Rosalind Franklin rover (launch 2028), which will drill 2m under the surface, below where UV and oxidants are, and below where energetic solar and galactic radiation can penetrate,’ he told MailOnline.

Professor Coates said Mars would be in his top three most likely worlds to host life in our solar system.

‘Mars had the right conditions 3.8 to 4 billion years ago – with evidence for water on the surface, CHNOPS [the six elements of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulfur make up 98 per cent of living matter on Earth] and energy – at about the same time life was starting on Earth,’ he added.

‘It is the nearest possibility for life beyond Earth. Even the cold night side on the Mars surface (about 150K) is warmer than the surfaces on Europa (140K), Enceladus (70K) and Titan (90K).

Professor Michael Garrett, of the University of Manchester, said: ‘There is probably no life above ground (Mars’ atmosphere is thin to absorb sterilizing UV radiation from the sun) but underground looks a better bet.

‘There is likely to be significant quantities of water underground and the temperature is also higher, so it’s possible some sort of basic life might be hiding there, like microbial life.’

How are we going to confirm either way?

In all likelihood, Perseverance. There are high hopes for the Mars rover, but it won’t be for another decade until we potentially get an answer.

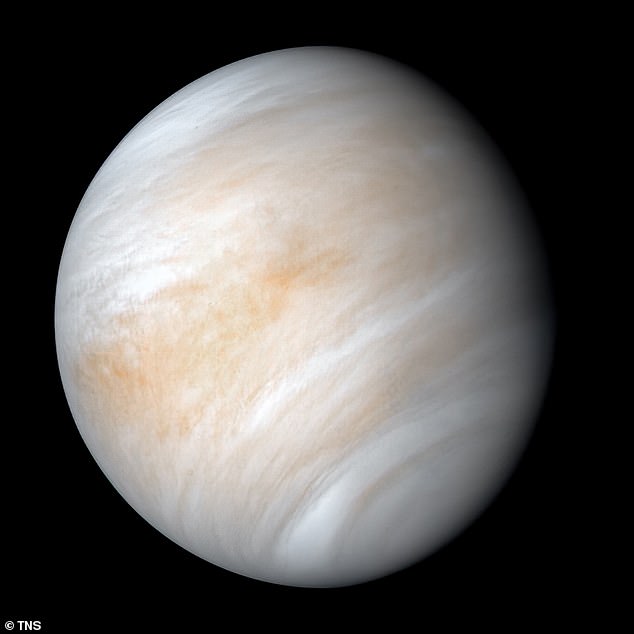

Venus

Earth’s closest neighbour and the second planet from the sun, Venus is a hellish world where surface temperatures are hot enough to melt lead and its atmosphere is thick with carbon dioxide.

But despite such inhospitable conditions, there has been a lot of excitement recently that it might in fact host a type of life in an unusual place.

Just over a year ago, a new study suggested that alien lifeforms ‘unlike anything we’ve ever seen’ may be living in the clouds of Earth’s ‘evil twin’.

Scientists claimed that the planet could be becoming ‘more habitable’ after identifying a chemical pathway by which life could neutralise Venus’ acidic environment, creating a self-sustaining, habitable pocket in the clouds.

For nearly 50 years experts have been baffled by the presence of ammonia, a colourless gas made of nitrogen and hydrogen, which was tentatively detected in Venus’ atmosphere in the 1970s.

At the heart of the confusion is that it should not be produced through any chemical process known on the hellish planet.

In the study by Cardiff University, MIT and Cambridge University, researchers modelled a set of chemical processes to show that if ammonia is present, the gas would create a cascade of reactions that would neutralise surrounding droplets of sulphuric acid.

If that were the case, this would then result in the acidity of the clouds dropping from -11 to zero, which although still very acidic on the pH scale, is a level that life could potentially survive at.

As for the source of ammonia itself, the authors believe the most plausible explanation is of biological origin, rather lightning or volcanic eruptions.

This chemistry suggests that life could be making its own environment on Venus.

‘No life that we know of could survive in the Venus droplets,’ said study co-author Sara Seager, from MIT.

‘But the point is, maybe some life is there, and is modifying its environment so that it is liveable.’

If the researchers are correct, the lifeforms are likely to be microbes similar to bacteria found on Earth.

However, a separate study by Cambridge University scientists – published in the summer of last year – claimed to have found no evidence of life in the planet’s clouds.

Any life form in sufficient abundance is expected to leave chemical fingerprints on a planet’s atmosphere as it consumes food and expels waste.

But the Cambridge experts found no sign of this in the atmospheric and biochemical models they used.

‘We wanted life to be a potential explanation [for the strange behaviour going on in Venus’ clouds], but when we ran the models, it isn’t a viable solution,’ said lead author Sean Jordan from Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy.

The debate rages on and will likely not end until the various hypotheses can be tested with proposed Venus-bound missions set to launch later this decade.

How are we going to confirm either way?

Two new NASA probes, coming in at a total cost of $500million (£352m), are set to blast-off later this decade and head for Venus. They have cool acronyms – DAVINCI+ and VERITAS – but they won’t actually be able to confirm the existence of life.

Despite this, scientists hope the information and findings they can gather will at least get us closer to answering that question more concretely.

VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy), will orbit Venus and peer through its thick clouds to map the surface.

Its aim is to understand the planet’s geological history and investigate why it developed so differently to Earth. The probe could also discover whether volcanoes and earthquakes are still happening on Venus.

DAVINCI+ (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging), meanwhile, will go one step further by actually landing on the hothouse world.

As it drops to the surface the high-tech probe will measure the planet’s acrid atmosphere to understand how it formed and evolved.

It will also aim to determine whether Venus — which is the hottest planet in the solar system with a surface temperature of 900°F (500°C) — ever had an ocean.

US company Rocket Lab is also developing the first privately-funded science mission to Venus called Venus Life Finder (VLF).

It will see a probe inserted into the planet’s hot, thick cloud layers to spend just five minutes searching for signs of habitable conditions.

The plan is for VLF to be launched in May this year and arrive at Venus in October, but if it misses this target lift-off date it will have to wait until the next launch window in January 2025.

Enceladus

You wouldn’t think that an object completely covered in ice would offer even the remotest chance of hosting life.

But although the surface of Enceladus is freezing cold, there is a lot of activity going on beneath it.

Scientists know this because Saturn’s sixth largest moon ejects liquid water, ice and organic material from its core out into space.

The organic molecules have been identified as nitrogen and oxygen-bearing compounds, similar to those involved in chemical reactions on Earth that produce the amino acids that are the building blocks of life.

The world is thought to have a vast salty, liquid water ocean hidden below its frozen crust, while NASA has also found evidence of hydrothermal activity deep underground.

This, scientists believe, could provide the source of heat needed to give life a chance to thrive.

‘If the conditions are right, these molecules coming from the deep ocean of Enceladus could be on the same reaction pathway as we see here on Earth,’ Nozair Khawaja, of the Free University of Berlin, has previously said.

He carried out research on data from NASA’s Cassini mission, which discovered the organic compounds during a 13-year mission that ended in 2017.

‘We don’t yet know if amino acids are needed for life beyond Earth, but finding the molecules that form amino acids is an important piece of the puzzle,’ Khawaja added.

Professor David Rothery, of the Open University, said he believed Enceladus was one of two worlds in our solar system most likely to harbour extraterrestrial lifeforms.

‘The big unknown is how likely it is for life to get started, if conditions are suitable for life,’ he told MailOnline.

‘However, Enceladus and Europa both have internal (below an ice shell) oceans sitting on top of tidally-heated (so warm) rock.

‘Chemical reactions between water and hot rock probably result in “hydrothermal vents” (hot springs) on the ocean floor, where microbes can feed off the chemical energy.

‘It doesn’t matter that sunlight can’t penetrate to those depths — we have similar “chemosynthetic life” clustered around hydrothermal vents on Earth’s sunless ocean floors too.

‘If there are microbes, maybe some more complex forms of life have evolved that eat the microbes.’

Professor Andrew Coates, of UCL, also said Enceladus was one of the leading contenders to host alien life.

‘The plumes discovered by Cassini-Huygens come from a subsurface salty ocean under the ice, and the mission also discovered evidence for silicates in the plumes, which likely come from vents on the ocean floor, perhaps a bit like black smokers on Earth,’ he told MailOnline.

‘Also hydrogen was directly found, completing CHNOPS at Enceladus. [The six elements of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and sulfur make up 98 per cent of living matter on Earth.]’

How are we going to confirm either way?

Unfortunately there aren’t currently any missions scheduled to study Enceladus. A number of proposals have been put forward, including several to NASA, but nothing has been picked to actually go to Saturn’s moon.

This is a shame, given that many scientists believe Enceladus to be one of the most likely candidates to host extra-terrestrial life.

If and when we ever do go there, digging into the ocean would be the best way to see if any lifeforms exist on the moon, although it might also be possible to detect biosignatures in cryovolcanoes.

These are volcanos that erupt vaporised materials such as water or ammonia rather than molten rock.

Europa

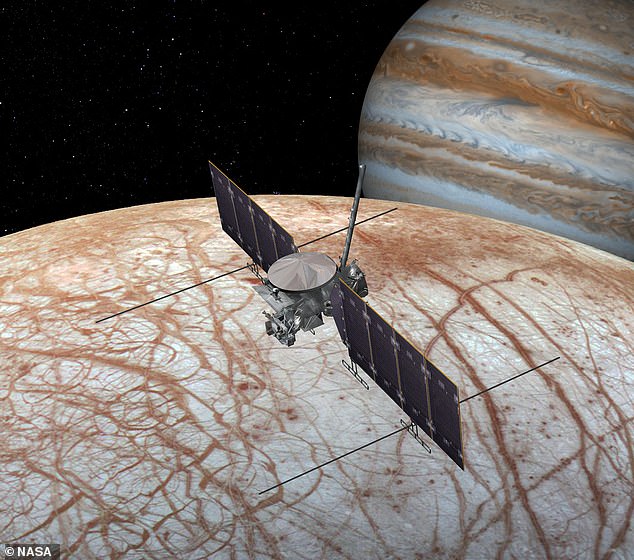

Another popular candidate to host alien life — and this time there might soon be an answer from missions scheduled to fly to it.

Europa is the smallest of Jupiter’s four Galilean moons but it is seen by most experts as the most likely to have the right ingredients for life.

Part of the reason is its massive subsurface, and potentially salty, ocean which is heated up by tidal forces.

This is believed to create an internal circulation system which keeps waters moving and replenishes the icy surface on a regular basis.

Such a theory is significant because it means scientists would not necessarily have to delve deep into the underground ocean to find evidence of life, as the fact that the ocean floor interacts with the surface means it could throw up clues there.

‘Of the Galilean satellites, Europa is the most likely [to have alien life] as the ocean is likely in contact with sand/rock according to models,’ Professor Coates told MailOnline, ‘whereas at Ganymede and Callisto the ocean floor would be ice due to lower temperature’.

He added that because Europa is bathed by Jupiter’s energetic radiation belts this too could be useful for emerging life, as it could result in oxygen potentially finding its way into the subsurface oceans.

Professor Garrett, of the University of Manchester, added: ‘The giant planets like Saturn and Jupiter tend to churn up the interiors of their icy moons, so there is a lot of mixing of water with carbon rich chemistry — but it would probably be microbial life, if there is any life at all.

‘If we do find life in the solar system, I wouldn’t be shocked if we discover it somewhere we think is least likely — new science is always full of surprises.’

How are we going to confirm either way?

NASA’s Europa Clipper will provide the best chance of confirming the existence of extraterrestrial life on Europa.

The spacecraft is due to launch in 2024 and reach the Jovian moon in 2030, at which point it will carry out a series of low-altitude flights to study the surface.

Clipper will also investigate the subsurface environment where possible, in an attempt to find signs of alien activity.

More data will also be provided by the European Space Agency’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) spacecraft, which is due to launch in April.

It will make two flybys of Europa during its time in the Jovian system and is set to explore three of Jupiter’s moons during its mission.

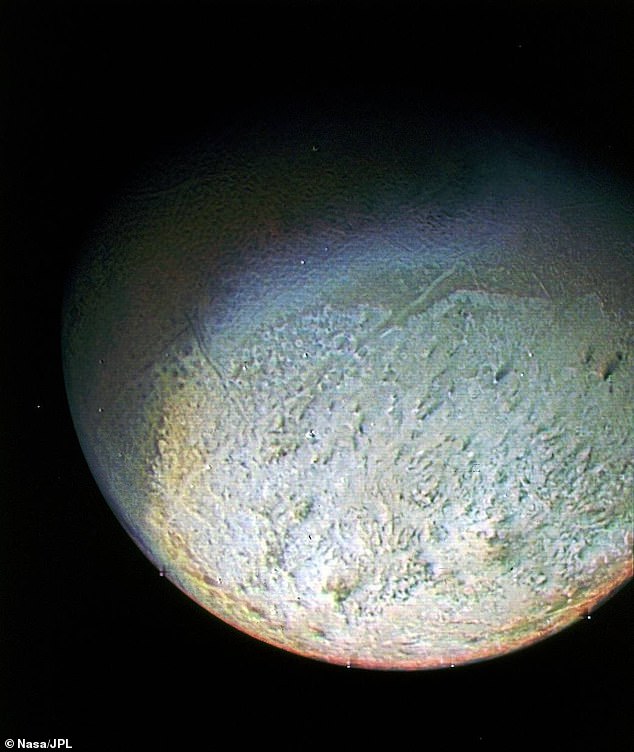

Triton

Now we’re going a bit further afield.

Triton is Neptune’s largest moon and one of just five natural satellites in our solar system confirmed to be geologically active.

Scientists know this because it has active geysers that spew out sublimated nitrogen gas.

Much like Enceladus, it is a freezing cold world. But that’s in part because it is so far from the sun, circling the most distant planet in our solar system.

Its surface is mostly frozen nitrogen, while it has water ice in its crust and an icy mantle.

However, because of a gravitational phenomenon known as tidal heating, it is thought to receive some heat from Neptune that could help warm its waters and create conditions possible for life.

An example of how this works elsewhere in the solar system is the gravitational tug-of-war between Jupiter’s moons and the planet itself, causing the natural satellites to stretch and squish enough to warm them.

It that some of the icy moons contain interiors warm enough to host oceans of liquid water, and in the case of the rocky moon Io, tidal heating melts rock into magma.

However, despite there being a possibility of alien microbes on Triton, the fact that the moon is so cold makes it unlikely anything could stay unfrozen for long enough to exist.

Most scientists agree that the world is pretty low down on the list of potential sources of extraterrestrial life.

How are we going to confirm either way?

Finding life on Triton seems highly unlikely, in part because the only mission to ever visit the world was Voyager 2 in 1989, and there is nothing else scheduled in the near future.

One of the main stumbling blocks for this is that the window for such a mission to Triton only opens every 13 years.

A concept to explore Triton, along with flybys of Jupiter and Neptune, was proposed to NASA in 2019.

However, the so-called Trident mission seems unlikely because it was beaten out by other concepts chosen by the US space agency, including the two probes to Venus.

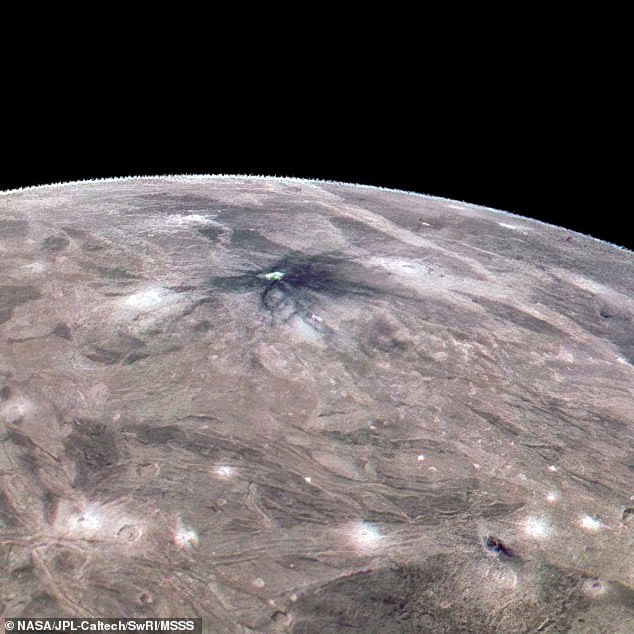

Ganymede

Not only is Ganymede Jupiter’s largest moon, it is also the biggest natural satellite in our entire solar system.

Like some of the other moons mentioned, Ganymede has an icy shell with secrets hidden beneath its surface.

Once again, it has a saltwater ocean so vast that it is believed to contain more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined, a potential breeding ground for life.

The moon also has two more things going for it which would be beneficial for any extraterrestrial lifeforms.

The first is an extremely thin oxygen atmosphere and the second is a magnetic field, something that is vital in protecting worlds from the sun’s radiation and an attribute that no other moon in the solar system has.

All very positive you may think.

The problem is that Ganymede is much colder than Earth, with daytime surface temperature ranging from 90 to 160 Kelvin (or -297 to -171 degrees Fahrenheit).

Not only that, but Jupiter and its moons receive less than 1/30th the amount of sunlight that the Earth does, and Ganymede has essentially no atmosphere to trap heat.

How are we going to confirm either way?

Sadly, there are no dedicated missions due to study Ganymede.

However, the JUICE mission mentioned above will take a close look at the moon when it enters its orbit in 2032.

The European spacecraft may have an opportunity to peer down at the surface and study Ganymede’s interior with radar, perhaps providing an insight into whether it is in any way habitable.

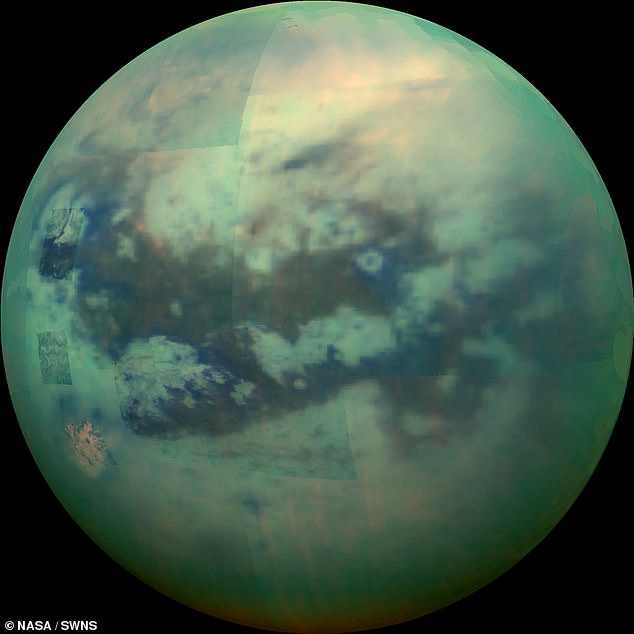

Titan

Saturn’s largest moon Titan is so huge it is actually bigger than the planet Mercury.

Interesting though that may be, what really makes the world exciting is that it is extremely rich in organic materials and possesses the sort of simple chemistry that is believed to have been vital in the creation of life on Earth.

Thanks to flybys from the Cassini spacecraft, experts have also found evidence of great lakes and signs of rain near the moon’s north pole, while it has one of the thickest atmospheres for a rocky world outside of Earth and Venus.

The methane in this atmosphere is what makes Titan’s chemistry possible, but where this gas comes from is a mystery.

Like other moons mentioned above, Titan is also thought to have a subsurface ocean that is around 35 to 50 miles (55 to 80 kilometres) below its icy ground.

On the surface, the world is teeming with lakes, rivers, and seas, but rather than being made of water these are actually liquid methane and ethane, providing a potentially habitable environment for life.

The only problem, once again, is that Titan is very cold. It is nine times further from the sun than Earth, so only receives about 1 per cent the amount of solar warming.

It all adds up to the theory that if there is extraterrestrial life on this world it will be very alien indeed, and certainly different to us.

That’s because anything on the surface would have to be ethane-based rather than water-based, and molecules such as DNA would not work.

Nevertheless, Titan still sits at the number 4 spot on Professor Coates’ list of worlds most likely to harbour extraterrestrial life, in part because of its thick atmosphere and prebiotic chemistry he told MailOnline.

Dr Joanna Barstow, of the Open University, also had Titan in her top three.

She told MailOnline: ‘I would consider Titan to be a contender because it is the only other body in the solar system to have surface lakes [besides Earth].

‘In the case of Titan, these are made of liquid hydrocarbons (methane and ethane) not water — but it isn’t impossible that life elsewhere could have evolved to make use of these liquids instead.

‘If there is anything there, we would expect it to be microorganisms.’

How are we going to confirm either way?

NASA’s mission to Titan, known as Dragonfly, will fly more than 100 miles around the celestial satellite. It was originally set to launch in 2026, but the Covid pandemic pushed back the launch date to 2027.

The mission will see the US space agency send a drone helicopter to explore Titan’s atmosphere from 2034 in an attempt to shed further light on the moon’s prebiotic chemistry.

The craft will explore diverse environments from organic dunes to the floor of an impact crater where liquid water and complex organic materials key to life once existed together for possibly tens of thousands of years.

It will also investigate the moon’s atmospheric and surface properties and its subsurface ocean and liquid reservoirs, while trying to search for chemical evidence of past or current life.

Callisto

The most fascinating fact about Jupiter’s moon Callisto is that it has the oldest surface of any world in our solar system, at about 4 billion years old.

That doesn’t have any real bearing on its potential for life, but it is another world thought to have a large ocean deep underground and an interesting atmosphere.

It is thin, but Callisto’s atmosphere is more Earth-like than most other moons in the solar system as it contains oxygen, hydrogen and carbon dioxide.

The drawback to there actually being life is again how cold the moon is.

In the past, scientists always thought Callisto was a boring ‘ugly duckling moon’ and a ‘hunk of rock and ice’ because it was a crater-covered world which didn’t seem to have much going on geologically.

The chance of it actually having life is less likely than some of the other planets and moons listed here, but it is certainly not seen as being as boring as it once was.

How are we going to confirm either way?

Once again, JUICE will offer the most insight. The spacecraft will make several close flybys of Callisto during its mission to carry out detailed observations of Jupiter and its three large ocean-bearing moons.

After a seven or eight-year cruise to Jupiter, utilising Earth and Venus gravity assists to get there, JUICE will go into orbit around the gas giant in 2031.

So we’ll have to wait another decade before we have any more clues as to whether they could be life on Callisto or Jupiter’s other moons.

Ceres

We’ve looked at the planets and moons that could host alien life in our solar system, but what if the most likely candidate is actually a dwarf planet?

It’s an interesting thought, but seems unlikely.

Scientists think Ceres – which sits between Mars and Jupiter – could be home to liquid water deep underground, perhaps around 25 miles below the surface.

If this is the case, it would almost certainly be extremely salty and therefore would stop the water from freezing.

Not only that, but NASA’s Dawn probe found evidence of organic compounds on Ceres while orbiting the world between 2015 and 2018.

As mentioned in relation to some of the other leading candidates for life above, this could provide the raw materials needed for life, but the world would need some heat source to actually create it.

Also working against Ceres is its size. The tiny dwarf planet is 13 times smaller than Earth, making it a complete mystery as to how the fraction of gravity on the world could affect any potential life.

How are we going to confirm either way?

As some of the interesting features about Ceres have only been discovered in the past decade, there is no mission currently scheduled to visit the dwarf planet.

So it will be a while before we get any concrete answers.

That being said, there has still been a series of proposals for how Ceres could be better studied by future missions.